The Female Orphan School: 1813 to 1850

The guiding mission of the institution was to train 'orphaned' girls with the skills they would need to work as domestic servants and escape the life of poverty, idleness, immorality and prostitution that it was thought would otherwise befall them. Whilst it was called the 'Female Orphan School', many of the girls did in fact have parents.

Governor King saw the purpose of the institution as the protection of the next generation of Australians:

"Finding the greater part of the children in this colony so much abandoned to every kind of wretchedness and vice, I perceived the absolute necessity of something being attempted to withdraw them from the vicious examples of their abandoned parents."

Its founders believed that educating these girls and training them with domestic skills would help create a more respectable working class and that the regimented routines and close monitoring that characterised the girls' lives at the school would produce obedient, productive workers for the growing colony. It was feared that unless the courses of these 'orphaned' girls' lives were corrected, the character of the future Australian society would be tainted. Reverend Samuel Marsden, who was responsible for the development of the school, put it this way:

"Remote, helpless, distressed and young, these are children of the State and though at present very low in the ranks of society, their future numerous progeny, if care is not taken of the parent stock, may by their preponderance over balance and root out the vile depravities bequeath'd by their vicious progenitors. Their numbers will in a very few years increase beyond that of the then existing convicts and what the character of this rising race shall be is therefore an extremely interesting thing."

When did the Female Orphan School move to Parramatta?

Before the Female Orphan School was built, the site was occupied by the Darug people. Governor Arthur Phillip granted a 60-acre portion of this land to Thomas Arndell, the surgeon in charge of the Parramatta Hospital. At this time, the land was known as Arthur's Hill.

When it was eventually decided to relocate the Female Orphan School, and sufficient funding was available, Governor Phillip Gidley King obtained this land as the site for the institution, granting a superior block of land in the Hawkesbury region to Thomas Arndell in exchange for his land at Arthur's Hill. The decision to relocate the school was based on the perception that the Sydney site was inappropriate. As the town of Sydney burgeoned, the position of the Female Orphan School in its centre became increasingly at odds with its founders' desire to protect the girls from the corrupting influence of urban society. Indeed, some clergymen worried that girls leaving the institution fared little better in life once they left it. Reverend William Pascoe Crook for example, claimed that many girls left the institution only to begin working as prostitutes.

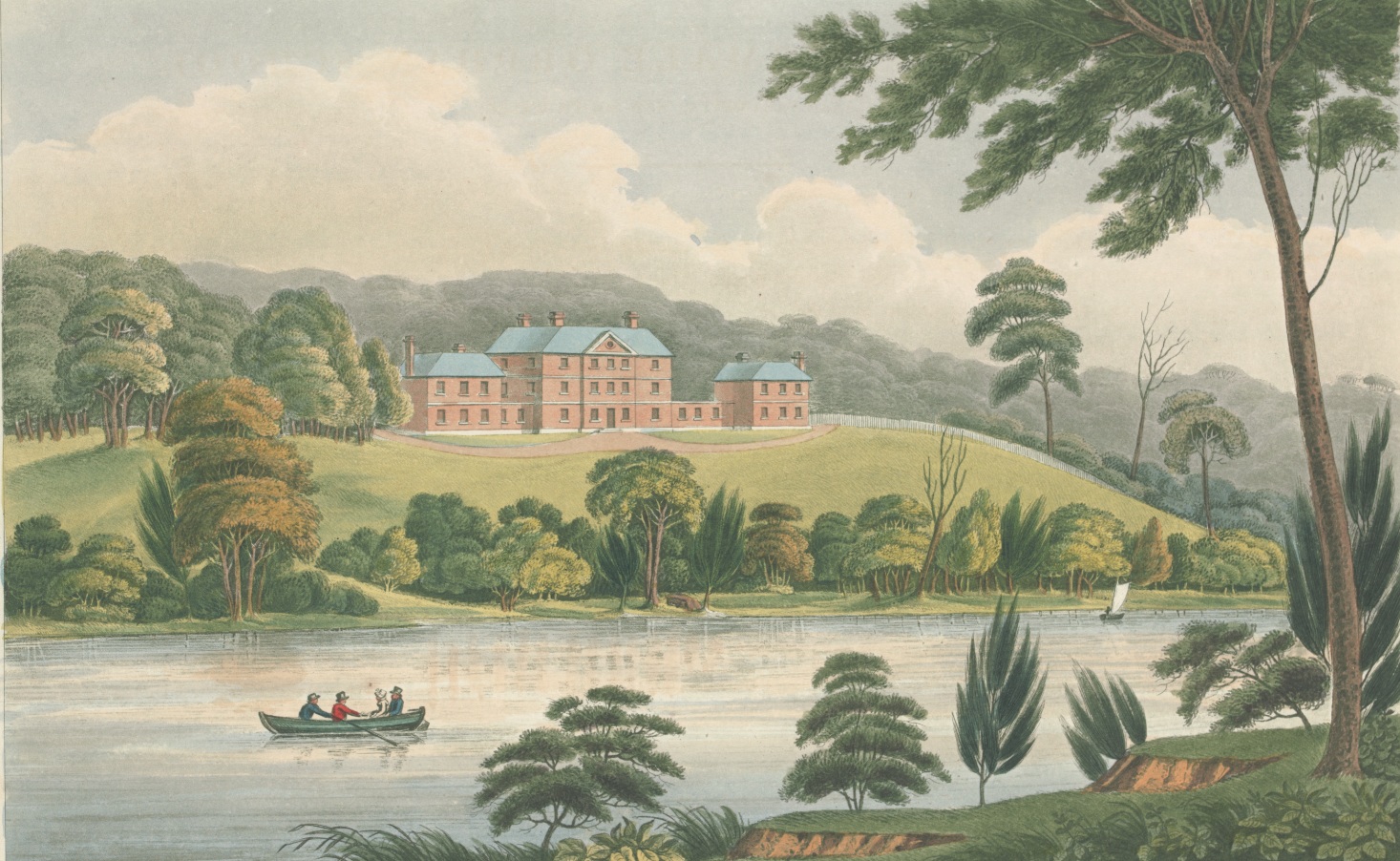

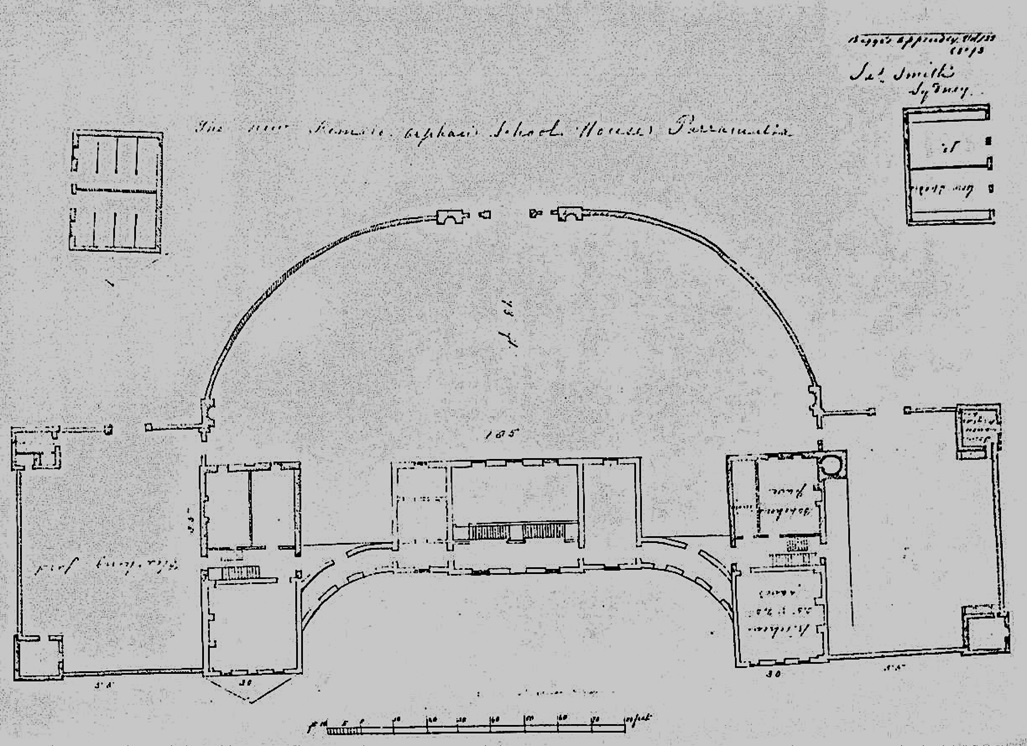

Construction of the Female Orphan School building began in 1813, at Arthur's Hill, atop a steep bank of the Parramatta River, just outside Parramatta itself. It is unclear who the building's architect was. The earliest, undated, plan of the new Female Orphan School at Parramatta was signed by James Smith, a Parramatta builder. In August 1813, tenders were called for the provision of 1000 bushels of lime, 20,000 feet of timber in boards, joists and scantlings, and 100,000 bricks. Governor Lachlan Macquarie himself laid the building's foundation stone the following month. The location of this foundation stone within the building remains unknown. Reverend Samuel Marsden oversaw the construction of the school, but day to day construction operations were supervised by builder James Elder. In 1814, Marsden wrote:

"I am now putting the roof on the Female Orphan House at Parramatta which will contain about two hundred girls. It is a noble building. If the young girls are only taken care of and kept from vice the colony will prosper."

Designed in the palladian style, the form of the building was inspired by 'Airds House,' the home in which Elizabeth Macquarie (wife of Governor Lachlan Macquarie) grew up. Although the design of the building has sometimes been associated with architect Francis Greenway, his arrival in the colony of New South Wales came after construction of the Female Orphan School began. However, it is possible that he was involved in the design of subsequent additions to the building.

Click on image above

While the building's external shell was complete within a year, the internal fit out proceeded more slowly. Reverend Marsden blamed the workers, who he described as 'generally drunken, worthless characters'. The delays were also likely due to Marsden's absence after being shipwrecked in New Zealand, as well as protracted disputes as to whether convict labour should be used for the project, whether builders should be paid in cash or with goods, and other disagreements over financing.

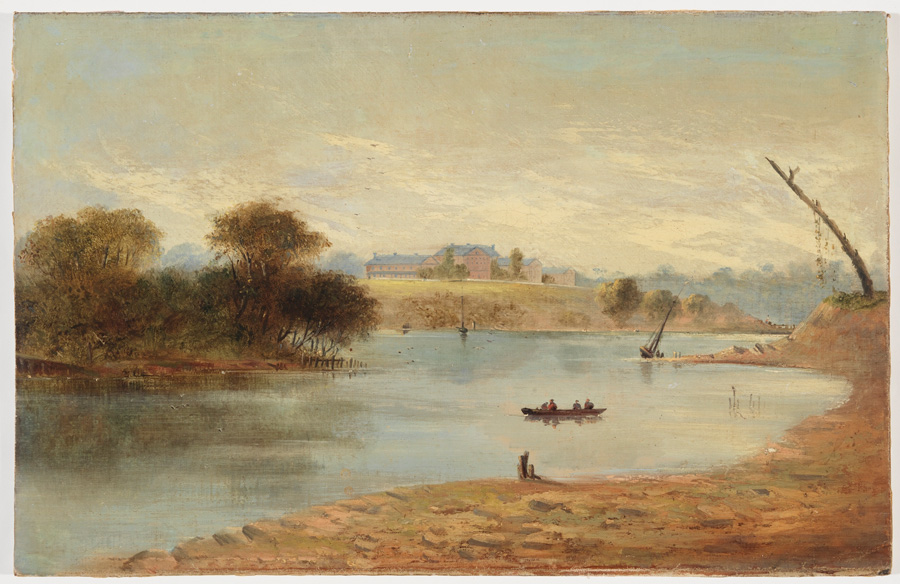

The building finally opened in 1818 and on June 30, 1818, the girls were taken on government boats along the Parramatta River to their new home at the purpose-built Female Orphan School building.

Click on the document above

There were problems with the building from the outset. Rising damp was a significant issue and there were not enough supporting buildings like stables. Work continued on the site after its opening – the necessary improvements and additional buildings were not completed until 1823. In some ways, the building was out of place – its unshaded windows were better suited to the dull skies of the Scottish highlands than the harsh Australian sun.

These issues notwithstanding, the Female Orphan School's imposing, yet elegant appearance won a great deal of praise throughout the young colony of New South Wales. Being the largest building in the colony at the time of its construction, it attracted significant attention. It was a prominent landmark on the river, and was visible on the road into Parramatta itself. The building was accessible either by boat, (landing at a jetty situated where the railway bridge now crosses the river), or by vehicle, using 'Orphan School Lane' (now James Ruse Drive). In accordance with the wishes of Mrs Elizabeth Macquarie, who was Patroness of the school, a fence was erected around it. Over time, the gardens around the building grew, planted with cuttings sent from the Royal Botanic Gardens. There were also orchards, wheat plantations and paddocks for livestock. These were established not only to train the girls in horticulture, agriculture and gardening, but also to supplement the school's food supply. As early as 1818, the school had 12 milking cows.

Who came to the Female Orphan School?

Whilst it was called the 'Female Orphan School', it has been estimated that fewer than 20 per cent of the girls living there were actually parentless. Two thirds of the girls had one parent living – often a mother who was living in severe poverty. The remaining girls had both living parents. Many children in 19th Century New South Wales were living in desperately poor conditions, and the employment opportunities for female convicts were often very limited. Girls were taken to the school for a range of reasons – because one of their parents had died and their remaining parent was ill, or unwilling to financially support them. Other girls came because one or both parents were convicts. In some instances, girls were admitted because one parent had died and the other had remarried. In other cases, a girl would be admitted to the school after her parents died during the long voyage to Australia from Britain. Some Aboriginal children were admitted having been referred to the school by a clergymen or magistrate. Aboriginal children were also admitted to the Native Institution at Blacktown. When the Native Institution closed in 1822, a number of Aboriginal children were transferred to the Female Orphan School.

Click on image above

In many instances, girls were admitted to the orphan school simply because their parents could not afford to care for them, or worked in jobs which made it impossible to do so. Women working as low-paid, live-in domestic servants as well as itinerant male workers and soldiers often found it very difficult to have their children live with them because of the nature of their work. In some cases, the masters of these servants would not allow them to have their children live with them, and so the children were sent to the Orphan School.

Because many sole parents had only recently arrived in the colony, they often had no extended family networks to help care for their children, although there were some informal systems of adoption and care for children. The majority of girls were admitted to the Female Orphan School voluntarily, in fact, most applications for admission into the school were submitted by the child's parent. This was not always possible as spaces were limited, and many applications had to be denied. Substantial paperwork and sometimes petitions were necessary for a girl to be admitted to the institution, and it was at the discretion of the council governing the organisation which girls were deserving of its care.

A number of girls at the orphan school were the daughters of women who worked at the Female Factory, a workhouse for convict women located in Parramatta. Women at the Female Factory kept their daughters until the age of three, or until they had been weaned, after which the girl was sent to the Female Orphan School. To some extent, this was because the authorities felt that convict women would have a corrupting influence on their children. There were clear rules about how a girl could be reunited with her mother, and indeed most mothers and daughters were reunited. However, the process was not necessarily straightforward and in some cases, a girl in the Female Orphan School would never see her mother again.

Click on images above

The age of the girls admitted to the Female Orphan School ranged between about 3 and 13 years old. In a time before universal public education, places at the Female Orphan School were greatly sought after, and many applications for admission were rejected. Applications for admission to the Female Orphan School can be read below.

Admission records from the Female Orphan School (State Records NSW SRNSW NRS782)

What was it like living in the Female Orphan School?

A uniform was designed for the girls to wear which was to be 'suitable to their condition in life - economical, plain and uniform'. The uniform consisted of a blue gown, a bonnet, a white apron and a white 'tippit' - a kind of cape which covered the shoulders and chest.

The girls' daily routine included training in gardening, cooking, domestic work, reading and writing. The girls practised needlework by making their own clothes, and by taking on sewing work from the public – work for which they received some payment. The girls were allocated time to play, and a small library was provided for older girls to use.

A typical daily routine generally proceeded as follows:

- 5:30am: Girls wake up (6:30am in the winter)

- 7:30am: Rooms are tidied, and girls are ready for their morning prayers, at which a psalm is read, followed by a hymn and a prayer reading

- Breakfast consisting of bread and tea

- 9:00am: Reading, writing, arithmetic scripture and other classes supervised by the Master

- 1:00pm: Lunch and play time

- 2:00pm: Sewing and other classes supervised by the Mistress

- 3:00pm: Domestic duties, needlework and gardening

- 6:00pm: Supper

- 7:00pm: Evening prayers, scripture reading and hymns

- 7:30pm: Girls go to bed

The education and training provided for the girls was much more limited in scope than that offered to their counterparts at the Male Orphan School in Liverpool. This reflects the social attitudes towards gender roles at the time. Girls too young for schooling were taken to the nursery, and sick girls (which in 1839 constituted a third of the school population) were kept in the school's infirmary.

Religious instruction was intended to be one of the core parts of life at the school, and the girls were reportedly taken by boat along the Parramatta River to church in Parramatta, though they were seated separately from other worshippers. How often the girls were actually taken to services is unclear. They were raised according to the teachings of the Church of England, regardless of their parents' faith. Opposition to this practice was one factor that led to the establishment of a separate Roman Catholic Orphanage at Bellevue Hill in 1837. Another factor was the provision of state funding for religious institutions of this nature.

The freedom the girls had to meet relatives and other visitors from the world outside varied over time. The school's 1825 rules stated that girls could see visitors only on the last Friday of every month, and that they visits must be conducted under the constant supervision of the Master or Mistress of the school.

Living conditions at the school also varied over time. The standard of the girls' education, hygiene and clothing depended on the management of the school, and at times this less than ideal. Despite the size of the new building, space was often limited, with up to three girls sharing one bed. There were periodic insect infestations and outbreaks of disease. Some contemporary reports record that many girls were 'afflicted with inflamed eyes' as well as 'eruptive diseases' on their heads. The cramped conditions and undeveloped understanding of hygiene during this time meant that a significant proportion of the girls were sick at any given time, and deaths from measles and scarlet fever were common in the 1830s in particular. The crowded conditions would only have exacerbated these problems. Whitewashing of the building's internal walls was regularly conducted, and this was intended to combat the spread of disease.

The girls' diet varied during the life of the institution. The school's 1818 rules stipulated that girls should receive a daily ration of one pint (½ a litre) of milk in the morning, and one pint of milk (or tea) in the evening, along with three quarters of a pound (about 340g) of bread, and half a pound (about 226g) of meat with vegetables, or rice or flour pudding once or twice a week. In the 1840s, the normal daily rations for each girl consisted of:

- 340g of flour

- 110g maize meal

- 225g meat

- 14g salt

- 7g tea

- 28g sugar

Extra rations were provided for holidays.

The methods by which discipline was enforced in the school also changed over its history. The school's 1825 General Rules stipulated that 'Corporal Punishment be very rarely resorted to'. The school's Master was to be the only person authorised to inflict corporal punishment and the child's name, misdemeanour and punishment was to be recorded on each occasion. These rules state that 'no child shall be punished with the loss of food', and that 'punishment shall generally consist of tasks to be performed after school hours'.

Later in its history, punishments were designed to be as public as possible in order to set an example to other girls, and create a sense of shame. Misbehaving girls could be allocated to the 'punishment class' – a group of girls which were made to wear a different uniform, prohibited from playing and made to sit separately from the others during prayers.

What happened to the girls when they left?

Many girls only stayed at the Female Orphan School for a year or two – perhaps sent there by their families during particularly financially strained times. Girls were to leave the Female Orphan School at the age of thirteen. By the time they left, they were to be able to 'read the Bible, write tolerably well and correctly, and work the simple rules of Arithmetic, as well as be competent to make Gowns, Shirts, etc. and perform other domestic duties'. When they left the school, the school's rules dictated that each girl 'shall be presented with a Bible, Prayer Book, dictionary, Grammar, and Arithmetic, and if particularly deserving with such other books as the King's Visitor may approve'. A significant proportion of the girls were sent to work as domestic servants for 'respectable' families, putting into practice the skills they had learnt at the school. Particularly promising girls went on to work as servants and teachers for the Female Orphan School itself.

Click on image above

Most girls were allowed to rejoin their families after leaving the school, or when their parents ceased to be convicts. Parents applying for their daughters' return had to demonstrate their good character and capacity to provide for their children and sometimes these applications were refused.

How was the Female Orphan School run?

- A vessel registration fee

- A duty paid for permission to sail into Botany Bay or the Hawkesbury River

- A fine for using convict labour without the appropriate permission

- A fine for open vessels carrying grain above the stipulated maximum weight

- A duty paid on the purchase of coal

- A fine paid for using defective weights and measures

- A levy paid on the export of timber

- A fine for polluting the Tank Stream by cleaning fish or keeping a pigsty nearby

- Fines imposed by magistrates and judges

- A duty on auction sales

- Alcohol import licence fees

This provided a revenue stream for the organisation that was independent of the budgetary allocations provided by the British government. It was this that made the construction of such a large building possible. The organisation was also funded through individual donations. In 1828, the Female Orphan School received a total of £2930 in government funding. Non-monetary support was also arranged by the government. If a stallion was loose and unclaimed by its owner within a week, it could be seized and donated to the Female Orphan School, and any pig found on the loose without a ring and yoke could also become the property of the school.

In its early years, the Female Orphan School was administered by a committee appointed by the Governor, and the daily operation of the institution was the responsibility of an appointed Master and Mistress (or Matron) of the school. The school's 1825 General Rules stated 'That Masters and Mistresses shall be required to treat the Children with kindness'.

The school was run with a staff that included teachers, cooks, laundry workers, gardeners and male convict servants who would tend to the farmland and livestock in the fields surrounding the building. When hiring staff, the Female Orphan School gave preference to married men and women.

Related Documents

- Website text with footnotes () PDF, 400.89 KB (opens in a new window)

Mobile options: